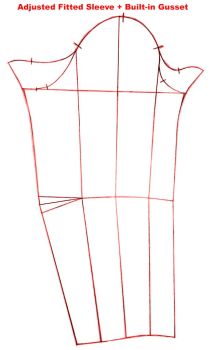

So, as I was saying, I also made some vanity tweaks to my Kenneth King fitted sleeve sloper, which led eventually to an experiment with sleeve gusset.

Slimming Down

While the fitted sleeve that was drafted as instructed is fine for most people, it has a little bit more ease in the upper arm & elbow than I wanted. Because my hip is relatively narrow, I want to de-emphasize my wider top to appear more proportional. My arms are relatively thin, so I thought I’d push the envelop & see how fitted I can go before it becomes a straitjacket. I slimmed the sleeve down a tinsy bit at the elbow instead of having a straight line going from bicep to wrist. This leaves me with 1-1/4″ ease at bicep, elbow, & wrist.

And here is a summary of the changes I’ve made…

The Legend of the Anatomical Armhole

OK, so I got the fitted sleeve to look how I wanted it now. But but can I move in it? I can bend my arms at the elbow. But arms up and arms forward not so much.

According to some, if the armhole is high & close to the arm joint, and the bodice armhole shape is anatomically correct (more scooped in the lower front, less in the lower back – so effectively oval pointing towards your bust), then that should give a decent range of motion. Mine is quite close to this. The only deviation is that the lower back portion of my armhole is also scooped a bit. I find normal armhole shape already a bit binding there (probably because of my Posterior Arm Joint). So to make it even more shallow in this fitted top sloper would be uncomfortable with my arms resting at the side never mind swinging my arm backward.

According to some, if the armhole is high & close to the arm joint, and the bodice armhole shape is anatomically correct (more scooped in the lower front, less in the lower back – so effectively oval pointing towards your bust), then that should give a decent range of motion. Mine is quite close to this. The only deviation is that the lower back portion of my armhole is also scooped a bit. I find normal armhole shape already a bit binding there (probably because of my Posterior Arm Joint). So to make it even more shallow in this fitted top sloper would be uncomfortable with my arms resting at the side never mind swinging my arm backward.

I think this “anatomically” correct armhole that people talk about needs clarification. The dress form that Bunka Fashion College and the Digital Human Research Center developed using 3D scans of the college’s students (so presumably as “anatomically” correct as can be) looks like the armhole I have on my Paper Tape Double dress form Q. So the “anatomical armhole” may not be in terms of the shape of the joint. It’s more likely to be about the typical forward movement that Fashion Incubator talks about in her book for design entrepreneur.

It seems like I’m not the only one confused by this subtle difference between static anatomy vs anatomy in motion. Someone else asked the same thing on Cutter & Tailor Forum about shape of the arm joint (like mine) vs the bodice armscye (scooped in the front but not in the back). Professional tailor Jeffrey Diduch confirms that it is indeed about the arm’s motion. He also posted an interesting old diagram showing how the arm joint shape may be affected by the posture…

So while in professionally tailored suit jackets the armholes are indeed shaped as prescribed by this “anatomical armhole” concept, even Jeffery warned not to over do it lest it creates a mess at the back armhole. And even with this allowance for forward arm movement, if you look at men in suit jackets raising their arms forward, the sleeves still look a bit binding. Almost everyone agree that you can’t have both total mobility AND a streamlined look. If you want a smart suits (in traditional woven) you’re not going to be able to play sport in it.

So what do I do about my straitjacket of a fitted top & sleeve°? I decided to give sleeve gusset a go to see if that improves mobility beyond 30° sideway & forward that my fitted sleeve gives me without adding messy folds at the armpits.

The Grand Gusset Experiment!

I’ve read about sleeve gusset before. But it was always in the context of a kimono sleeve. Kenneth King’s Basic Sleeve CD Book is really the first time I came across the concept of a built-in / cut-on gusset for fitted set-in sleeves. It promised slim sleeves with decent mobility. He says it’s used frequently in bridalwear where the bride want to look svelte but still need to be able to raise her arm to dance with her Husband or Dad. There was instruction for drafting such pattern, but no photo demonstrating what it looks like when worn. My interest was piqued, but Google found very little additional info on this technique. To save you some hassle, here are the best links I found…

On built-in / cut-on gusset (aka “pivot sleeve” ?):

- Kenneth King 2-piece pivot sleeve on a jacket (different shape / instruction than the Basic Sleeve CD Book as it’s for 2-piece sleeves), and Fashion Incubator’s comment on this type of sleeve gusset. (There’s another type of 2-piece pivot sleeve in The Modern Tailor Outfitter and Clothier – Vol 1 that’s sort of similar concept, but shaped differently. The description says it’s “chiefly confined to sporting coats, such as are used for shooting and golfing” and “the finished appearance is very much like the ordinary sleeve, excepting that a deep pleat is formed in the underside at back scye.”)

- A historical costume reference to gusset for fitted sleeves, both separate gusset & built-in “flare”. Interestingly their 1-piece fitted sleeve is cut with the sleeve seam in a different place – looks like the back sleeve seam of a 2-piece sleeve.

- “The Poetry of Sleeves”, by Rebecca Nebesar, Threads issue 9 Feb/Mar 1987, p24-29 on Threads Archive DVD. This one looks like Kenneth’s 1-piece sleeve built-in gusset, but joins up with the original sleeve seam at the bicep rather than a little bit further down.

- “A Ball Gown Built for Comfort”, by Karen Seaton, Threads issue 51 Feb/Mar 1994, p36-39 on Threads Archive DVD. Mine end up looking most like the illustration for this one, but the instruction says to determine the shape when you’re fitting the sleeve on the wearer, so maybe it doesn’t always come out the same shape.

- Built-in gusset also seems to be used in dance costumes as well. Here’s an pattern instruction for “Dance Sleeve Gusset”. Note how the gusset shape is flipped vertically, so you have 3 mountains! Look really odd so I didn’t try it. But Wild Ginger Pattern Software also suggest the same type of built-in gusset.

- And finally, an informative advice from a theater costume professional on Cutter & Tailor forum about gusset, high armhole, and range of motion. Not many sources mention the different solutions needed for sideway vs forward range of motion…”Yes it is possible to cut high armholes with gussets- we do it all the time for theatre. I doubt though if many “regular” tailors do…In terms of movement and sleeves you have to determine if you need forward reaching movement or raising your arms above the head movement. They require different manipulations.Reaching forward requies a longer hindarm and that is usually accomplished with a sleeve that has a shallower sleeve cap height and is therefore wider in the upper arm as well. This can be done and doesn’t have to look messy- I think it gets messy when the shoulders aren’t fit properly, along with an excess of back width, and the extra length in the back of the sleeve all combined.Reaching upwards requires more length at the front and front underarm area with little extra length added at the back. If done correctly this kind of a gusset is barely noticable when the arm is at rest. The width of the sleeve is not noticeably changed.”

On separate gusset piece for set-in sleeves:

- Fashion Incubator’s version of the set-in sleeve gusset is more (American) football shape than diamond shape of traditional kimono sleeve gusset. But it’s shown for a looser fitting shirt. Part 2 of the article here.

- This blog article about raising the armhole also went for football shape gusset. It has a link to a more fitted dress supposedly with set-in sleeve gusset.

- “Add a Gusset to a Sew-In Sleeve”, by Kenneth King, Threads issue 156 . Sadly it’s not on my Threads Archive DVD & requires login for online viewing, so I haven’t read this article 🙁 In the teaser photo the gusset looks like a 2-piece – ie with a fish-eye dart in the middle.

In the interest of sewing science progress, here is a summary of my experiment with both built-in & separate football shape gussets, + san gusset as experiment control…

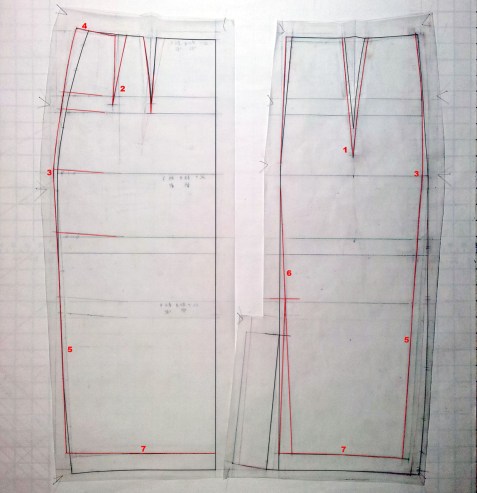

The Patterns:

As you can see, mine are hodge-podge of the different gusset approaches. So many experts, so many options, how does a girl choose, right? 😉

My built-in gusset started out like Kenneth’s. But because of the alteration done for my Posterior Arm Joint (shifting sleeve seam towards the front), it wasn’t clear where the pointed bit of the gusset should be – should it shift with the seam? Also the angle of the gusset at the sleeve seam became quite extreme with this alteration & difficult to sew. So, I end up rounding the gusset near the sleeve seam like the Dance Sleeve / Wild Ginger version, but with a more gradual transition rather than a sharp turn into the two mini-mountains to make it easier to sew.

My separate gusset is football shaped. But given the shape of my bodice armhole it became too deep & round. I was worried about the amount of extra fabric, so decided to add the fish-eye dart that’s sometimes used for traditional kimono sleeve gusset.

Les Mugs:

Observations:

- Both gussets help with sideway motion.

- Forward motion is definitely still restricted, with strains that seem to radiate from the armpit & run across the front bicep. It’s the same type of wrinkles I observe on men’s jacket, even on the well tailored ones. So I presume that if you pick fitted sleeve with deep sleeve cap, then there’s no way to eliminate the strain entirely.

- Both are fairly inconspicuous with arms at the side.

- I can definitely feel the gusset fabric against my armpits when the armhole is already cut high. There doesn’t seem to be much difference between the two gussets I tested despite one being on the bias. So it’s an acquired taste. Not for the slouching days! Perhaps if the gusset merge back into the original sleeve seam further down rather than at the bicep (ie increase bicep width slightly), then the gusset won’t press so closely to the armpits? Experiment for another day / someone else!

- The football shape gusset which has bias going in a different direction than the built-in gusset offers marginally more mobility.

- The football shape gusset which has a horizontal fish-eye dart to cut down on fabric bunching looks so ugly when the arms are up! The built-in gusset, on the other hand, looks rather cool when the arms are up.

In conclusion

I think I’m more inclined to go with built-in gusset if I were to make any woven, normal grain tops with very fitted sleeves. It’ll definitely be good enough for my desk job, and is OKish for holding on to handrails on public transport.

I wonder though, what if the sleeve is cut on the bias? I mean fitted kimono sleeve are sometimes at an angle to the bodice right? So surely they must be on the bias? Will a set-in sleeve cut on the bias with built-in gusset give me even more range of motion? Or will it just give me loads of other griefs?

To Cap Ease or Not to Cap Ease

To Cap Ease or Not to Cap Ease